Attorney General Merrick Garland and FBI Director Christopher A. Wray told Biden they were indeed concerned Iran might have recruited the man who fired at Trump during his rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, according to three people with knowledge of the briefing. Hours earlier, in fact, FBI agents had rushed to Texas in the middle of the night to interview an alleged Iranian operative the bureau had arrested Friday on suspicion of recruiting hit men to kill U.S. politicians, two said. Wray, appearing by video feed, said they had found no clear link between the shooter and the Iran plot, but they continued to run down every possibility.

This account reveals previously unreported details about the urgent efforts to find any possible Iran connection — though after months of investigation and extraordinary steps, the bureau ultimately concluded there was none — and determine what motivated the shooter.

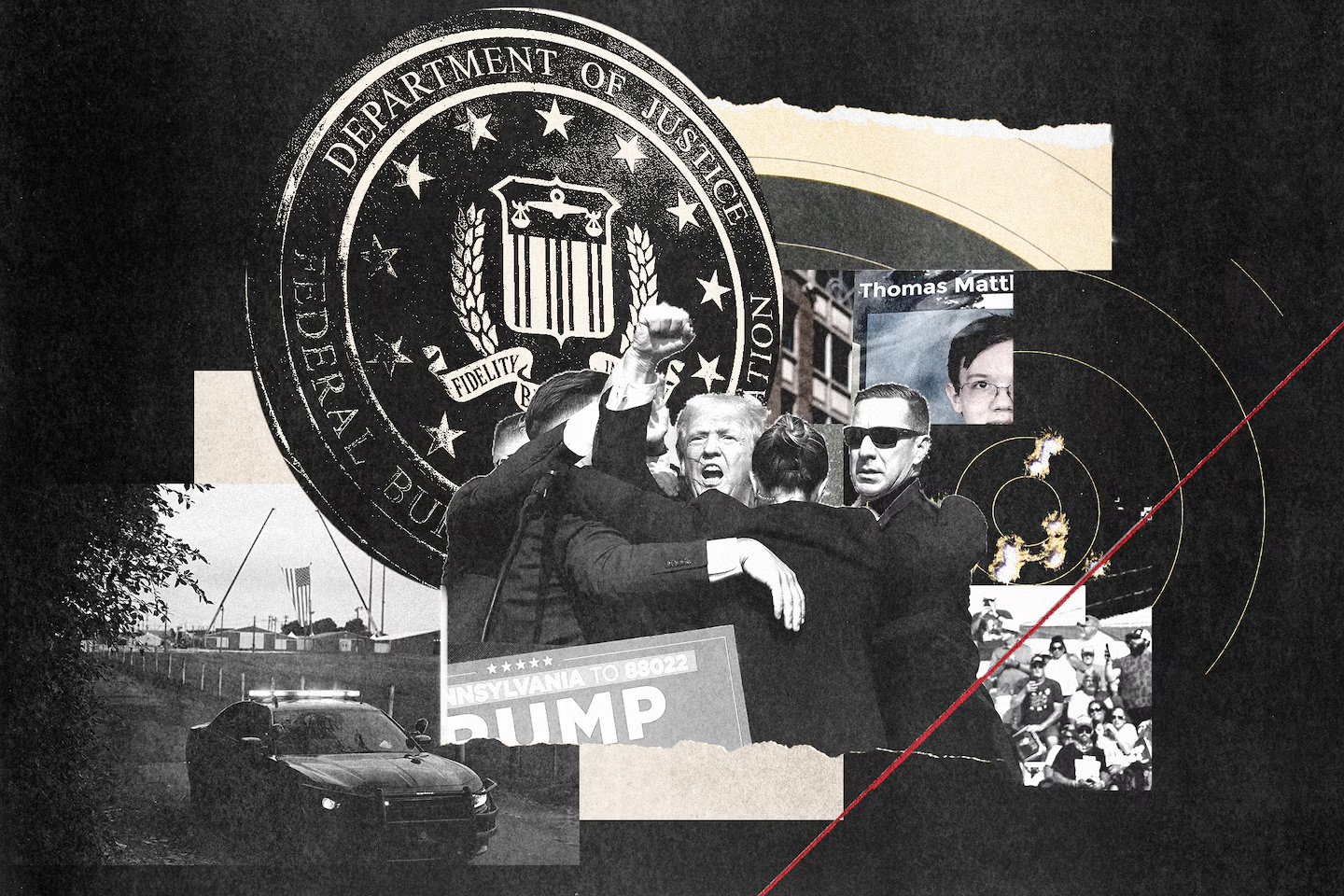

A year later, largely by process of elimination, investigators have concluded that Thomas Matthew Crooks, 20, acted alone. Crooks left no writings explaining his actions, but officials said he fit a profile of assassins the bureau has studied: socially isolated, educated but friendless, motived not by politics or ideology but by a sense of insignificance and a desire to become known. He was fatally shot by a Secret Service countersniper after he wounded Trump and killed rally attendee Corey Comperatore.

“The most frustrating thing in the world for law enforcement is not getting an answer on what caused this,” said one former FBI official, who like some others interviewed for this report spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters. “We just can’t quite say for certain, but that’s where all the evidence points to.”

The case remains classified as open, but a current senior FBI official said no new leads are being actively mined.

“Absent anything new, there’s not much to do,” the official said.

The lack of a clear, definitive motive has spawned numerous conspiracy theories and led to suspicions among some Trump supporters that the FBI was withholding information about the gunman, a registered Republican who also donated $15 to a Democratic organization and spent weeks planning an attack on the once and future Republican president.

As a high school student, Crooks scored a 1530 on his SAT, putting him in the top 1 percent of all test takers. He earned straight A’s at his community college near Pittsburgh and won plaudits from teachers, as when he designed a complex Braille chessboard. Yet starting in the month he turned 16 he was searching online for information about explosives, and in the year before the shooting he was trying to buy chemicals for homemade bombs. He also searched the internet for information about major depressive disorder.

The investigation ran around-the-clock in the early weeks, with Wray getting briefed at all hours by his deputy director, Paul Abbate, and chief of staff, Jonathan Lenzner. It consumed FBI agents and analysts from half of the bureau’s field offices, nearly every headquarters division and some international offices. Early on, in the hopes of tamping down baseless speculation, FBI leaders decided to share far more details about the probe than they typically would.

Within two weeks, the FBI had conducted over 450 interviews, including with witnesses, neighbors, classmates, teachers and family members, and had served legal requests on 64 companies to obtain phone, email, gaming and other accounts linked to Crooks.

By late August, six weeks after the shooting, agents had interviewed about 1,000 people, accessed Crooks’s communications on three encrypted applications, and gained an understanding of his interests and obsessions as revealed through hundreds of his computer searches.

Yet in some respects, Crooks remained a cipher.

“I remember thinking, ‘We have all of the tools and investigative power of the mighty United States trained on this 20-year-old kid. And we just don’t know,’” said one former law enforcement official involved in the probe. “That’s kind of scary.”

Just before 11 p.m. on the night of the shooting, Matthew Crooks called 911 to report that his son had not returned home nearly 10 hours after saying he was going to the shooting range.

Federal agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, along with local police, were already stationed outside the Crooks home in Bethel Park, Pennsylvania, about 50 miles south of the Butler fairgrounds, surveilling it and waiting for a warrant.

ATF agents had been dispatched to the home about 9:20 p.m. after determining that Matthew Crooks owned the rifle that was used in the shooting. But while the agents were en route, investigators found that the driver’s license picture for his son, Thomas Crooks, appeared to match the dead shooter.

When the father called 911 for help, the agents changed their strategy and walked up to his front door, according to an account one gave to a House task force that investigated the attack.

The father opened the screen door and said instantly: “Is it true? Did Thomas shoot Trump?”

“What makes you say that?” the agent asked.

“The news called me,” Crooks said, then invited them inside to conduct a sweep of his tidy brick home.

Inside, the ATF agent opened the door to Thomas Crooks’s bedroom. He saw at the foot of the bed a .50-caliber military-grade ammunition can with a white wire coming out of it, which he suspected was a homemade bomb. He spotted a one-gallon jug with a black label reading “nitromethane,” a volatile fuel, in an open closet. The agent ordered the house evacuated and summoned the county bomb squad.

Close to midnight, agents began interviewing Thomas Crooks’s parents.

Agents asked Matthew Crooks run-of-the-mill questions: names of his son’s friends, if his son ever had a girlfriend, if he knew about his son’s co-workers or workplace. The father said that he didn’t know anyone in his son’s life and that he and his son didn’t talk about friends or work.

“No, I don’t know anything about my son,” the agent recalled the father saying.

That same night, prosecutors at the U.S. attorney’s office in the Western District of Pennsylvania were busy opening a grand jury probe to gather as much evidence as possible about Thomas Crooks and his communications, even though he was dead and it wasn’t clear that anyone would face charges.

About 2 a.m., prosecutors in the Pittsburgh-based office were drafting a search warrant for the Crooks house, the first in a series of searches they would use to obtain the gunman’s phones and laptop so they could better trace his activity in the weeks leading up to the shooting.

***

From the earliest moments of the probe, investigators viewed the possibility of an Iran connection as urgent to figure out. Tehran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps had vowed revenge against Trump and his top advisers for the U.S. government’s 2020 drone strike that killed Gen. Qasem Soleimani in Baghdad.

Senior government leaders braced for fallout if the FBI were to learn Iran had orchestrated the hit, three administration officials said. “It would mean war,” one said.

Alarm that Iran may have been involved was heightened by the arrest — one day before the assassination attempt — of Asif Merchant, the alleged Iranian operative accused of plotting to kill U.S. politicians.

Merchant, a Pakistani national, had boasted to undercover FBI agents posing as hit men that he was recruiting others like them, according to court documents. Merchant had told the undercover agents he planned to leave the U.S. and would relay instructions to them about whom to kill and where after he was gone. Agents arrested him midday on Friday, July 12, in Houston as he was loading his luggage to go to the airport. He has since pleaded not guilty.

Before dawn on Sunday, July 14, just hours after the Butler shooting, FBI agents were dispatched to Merchant’s jail cell in Texas and took the extraordinary step of interviewing him without his lawyer to determine whether he knew Crooks, according to one person briefed on the interview. Citing a potential threat to public safety, they invoked special authority under Justice Department policy to question him while he was in custody and without some standard legal rights, according to two people familiar with the interview.

Agents continued questioning Merchant after he was formally charged with a murder-for-hire plot and transferred to federal detention in Brooklyn. An FBI summary of a July 17 interview was leaked to Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), who briefly posted it online before the FBI asked that it be removed. The Washington Post retrieved the summary, which is partially redacted, from internet archives.

According to the FBI document, Merchant said he had agreed to help the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps arrange to recruit hit men and pay up to $1 million to kill American political figures.

Though his Iranian handler had not said so outright, Merchant said he inferred that the ultimate target was Trump and that the plot was connected to Soleimani’s death. Merchant said he reported back to his handler his assessment of Trump security after watching videos of a Trump rally: 30 security guards, 20 cameras, four to five areas where audience members had to be scanned for weapons.